Dear Grandmother,

(Bunica, in your language)We never met;

you died long before I was born. Yet I am your namesake.Do we have anything in common?I feel a kinship to you, your life flowing

through my veins.

But do we share anything besides

a name and DNA?We share my father, your only son.

He was inspiring to each of us.

Though I knew him for only 12 years.He died young, like his father.

Heart disease runs in the family.

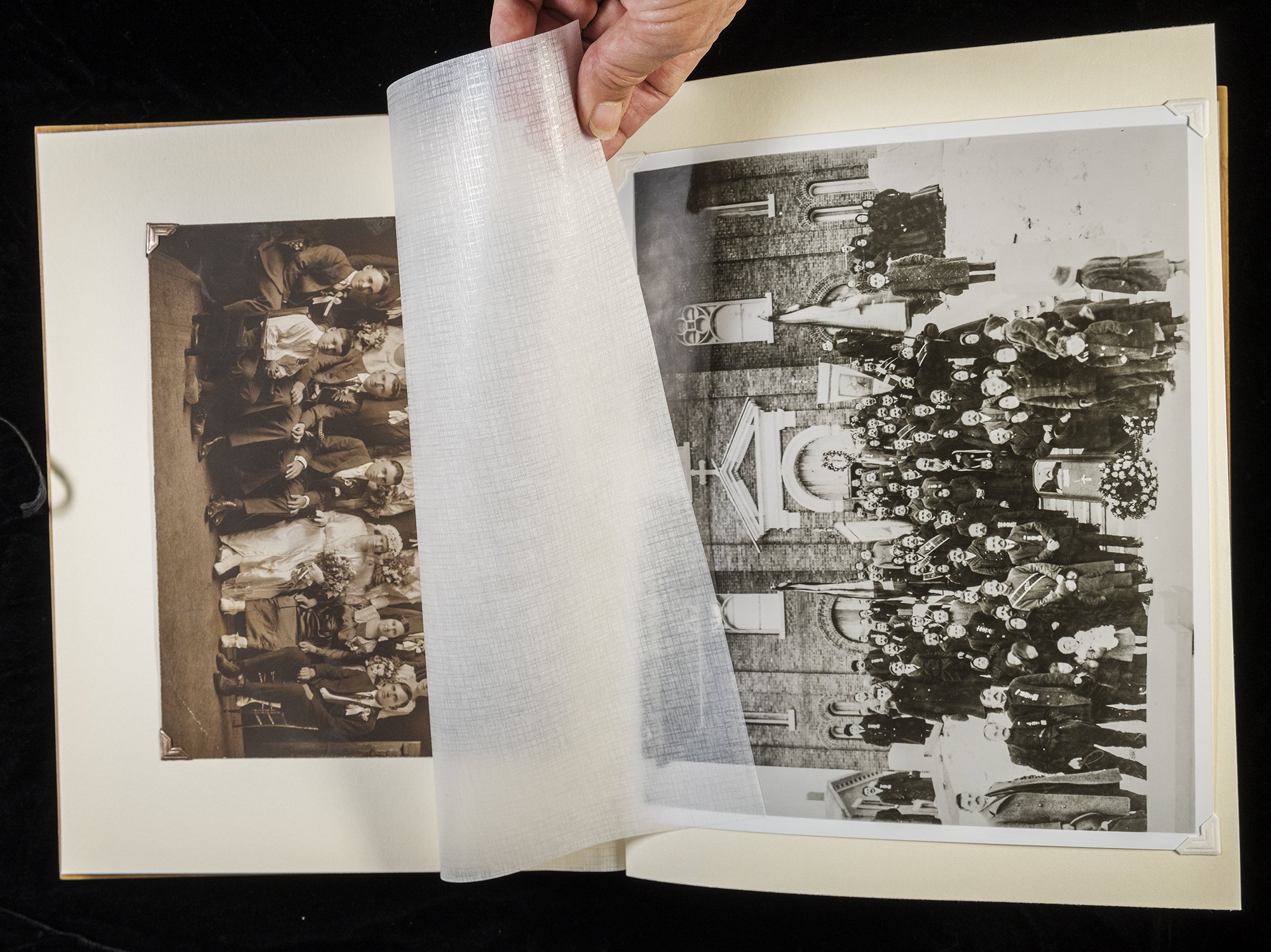

You lost a husband, I lost my dad.I have that picture of

my grandfather’s funeral.

Him in his casket,

on display

outside the church.

All of you mourners crowded

around him,

on the steps with a cross

and the bell tower behind you.

I see your tiny figures.

Amongst them, You,

with your black dress and headscarf;My aunt, 12 years old,

like me,

Dumbstruck

by the sudden death

of a parent.

And the tiniest figure of all,

my father,

age 3.What did he remember of his father?

I don’t recall him talking much about him.

Or even you, for that matter.

I’m sorry.

But maybe I didn’t listen. The other photographs I have of you

are portraits.

The later one,

perhaps you remember,

is a group shot of you

and your descendants

from your first marriage

back in Romania.

You, still in your black

Headscarf,

seated aside your eldest daughter,

whom I heard was the last

to immigrate to the U.S.,

flanked by her four children,

your grandchildren

at the time.

Those are the people

that I would

come to know. Much later in life,

your granddaughter named

Emilia

rekindled my

Connection

to the family.

There’s that name again.

Sometimes shortened to

‘Em’

as in her case,

or

‘Emma’

in your case.

Or anglicized to

‘Emily’

in my case.

This particular

‘Emilia’

we called

‘Aunt Em.’“Long time I’ve spent

searching

for the kind of gold

that fills a void –

an empty page,

a hole in the heart.

Maybe it’s found in a name……”

The other portrait I have of you

is just a small

Photocopy

on cheap paper.

Aunt Em sent it to me,

before she died.

Where is the original?You are older here.

50s? 60s?

This is the only time I see you

without the headscarf.

When did you stop wearing it?

Or did someone,

perhaps a relative with a hand-held camera,

come upon you before you had a chance

to put it on?

I like the ruffled collar

on your dress.

Perhaps you were letting loose.

Somewhat. After a life of hardship;

two husbands dead,

a peasant’s existence in your

Homeland,

an arduous and anxious

Journey

to a new country;

back-breaking work there,

to make a living

without knowing the culture,

the language,

while raising two children,

Alone.I know my dad helped.

A lot.

He told me he started work

at age 5.

He sold apples door to door.

He got a paper route.

He searched for scrap metal

on the railroad tracks

near your home,

which he could exchange

for coins. This he did to supplement your

cleaning jobs

and your factory work.Besides the funeral photograph,

I have three other images

from my dad’s childhood.

One is a group portrait

of his cousin Loui’s wedding party.

It’s dated 1921,

so he must have been

about 8 years old.

He sits in the front row, on the far left.

What was his role in the wedding?

Ringbearer?Lastly.

My favorite photo is the vignetted

portrait of you and my dad,

probably done in a studio

when he was about 5.

It must have been a reach

Financially

to have this photo done

at that time.

My dad kept this picture

All the rest of his life,

under the glass on

the top of his dresser drawers.“Long time I’ve spent

searching

for the kind of gold

that fills a void –

an empty page,

a hole in the heart.

Maybe I find it in a face……”

A lucky stroke was when,

as an adult,

I discovered

my dad’s

Diary.

I hadn’t known that it existed.

Most of it is filled with poems

that he collected.

I never knew

he liked poetry.

Did you, Bunica?

But two pages

are a memorial to you,

after your death.

He writes of an endearing, enduring

relationship.

I learned more about

your lives

Together

than he ever told me.

How food was a comfort,

but often,

not enough.

That your house

had no hot, running water.

How he used to read to you,

because you could not.

That you still spoke

Romanian to each other.

And the only thing

you really enjoyed doing

was sewing or darning his clothes.

How you would wait,

seated at the window,

for him to come

Home

from school or work

each night.

That you had stairs

in the house

which were difficult

for you,

as you aged.This is all I can glean,

Bunica,

about your life

and my father’s early years,

from these six photographs,

Dad’s diary,

and some scattered stories

told through the years.Still - I wonder.

What do you and I have in common?

Would we get along if you were here now?

Or if I were there then?

Would you understand the things I do?

Would I like what you do? So –I’ve made up my own photographs.

I am you in your native country.

I am you as a new immigrant.

You are experiencing the world I live in.

You become part of my life.